Devastation & Desperation: The Emotional Fallout of Sending Your Daughter to Treatment.

December 29, 2021 will go down as one of the hardest days of my life. This marks the day Andrew and I drove our 14-year daughter, Sydney, to a residential treatment center and left her there indefinitely. No amount of schooling, meditation, or thought work can prepare a parent for a moment like this. The entire day passed in slow motion. I carefully and methodically went from one moment to the next, actively avoiding any feeling. I would crumble if I allowed the tiniest of emotions to sneak into my consciousness. At 2:00, Andrew, Sydney, and I packed the car and drove in silence. The three of us didn’t speak as we carried her luggage from the car to the front door of Sydney’s temporary home. She was calmer than I expected. She was simultaneously brave and scared as she entered the unknown. I’m not sure if she knew that I, too, was scared of what the next 4-6 weeks would look like. I remember the look in her eyes (that’s all I could see, as we had masks on during the admittance process). She kept looking at me, then Andrew, and occasionally at the man checking us in… her soon-to-be therapist. I think she was in disbelief that we actually went through with it. After we completed the paperwork and provided payment, as if we were dropping our dogs off for boarding, he said to us, “I will give you space to say goodbye.” He took half a step back and allowed us approximately 4 square feet to say goodbye to Sydney. She cried, I cried, and Andrew looked at the ground for as long as he could. She gave me the first real hug she’s given me in over 3 years, and I hung on tightly for just a little too long because at that moment, nothing mattered more than her knowing how much I love her. We then walked out the door without our child, without any reassurances, and without any guarantees that this traumatic plan would help Sydney find peace and healing.

It was raining, which is a rarity in California. Usually, I would scurry to the car as if the rain might pierce my skin if I stayed in it too long. On this day, I walked slowly because if the rain could penetrate my skin…I wasn’t sure it mattered at that moment. I looked up as I got in the car, and the neighbor was looking out her window. She was staring at us, and I couldn’t help but wonder what she was thinking. “Another fucked up family” or “I wonder what their kid is in treatment for.” Perhaps she was taking pity on us. I knew I didn’t care, but it bothered me nonetheless. Andrew and I drove home in silence. There was nothing to say, no small talk to be had, and neither of us was in a position to try and make the other one feel better. We were both hurting, we were both worried, and we were both drained as hell.

The weeks leading up to her admittance were torture. I sat at my computer in early December and filled out the online application for this particular facility as tears ran down my face. This isn’t something parents plan for or dream about when their child is a baby. These decisions are made when you are desperate to save your child and your relationship with her. Every decision you make is painful and leaves you feeling as if you screwed up somewhere along the way. I submitted the application and secretly hoped they would call and tell me she needed outpatient treatment. I wanted the doctors and therapists to determine that her case wasn’t severe enough for residential. I anxiously awaited their phone call. Around a week later, they informed us that she was “accepted” and “residential” was the recommended level of treatment. FUCK! We didn’t celebrate the admittance with champagne like a college application. I accepted the news with silence, more tears, and a growing feeling that I could vomit at any moment.

The following day Andrew and I quietly drove to tour the facility, a home in a nice neighborhood not far from Sydney’s school. We were greeted by the director, who kindly answered our questions and showed us around the house. I was surprised that the teens in the home looked “normal.” I’m not sure if I expected monsters or Marilyn Manson lookalikes, but they were undoubtedly average-looking kids. I’m not sure if this brought relief or a more significant bout of curiosity as to why so many teens are suffering, and yet, no one is talking about it. We finished the tour, got in our car, and drove home. We didn’t talk much, but I remember saying, “We can’t turn on each other. This is going to be hard, and we can’t take it out on one other…we can’t blame each other; we just need to be there for one another.” Andrew agreed and drove back to work. I didn’t make it inside before the tears came. I couldn’t figure out how I would drive away and leave my child with strangers. How was this the answer? How would this help? How the hell was this happening to my family?

We knew Sydney was entering Residential treatment for almost four weeks before she left and before we told Sydney of these plans. We went through school performances, basketball games, holiday parties, and Christmas knowing we were sending our child away to a treatment center, and she was clueless. We were simply waiting on a call from the facility to inform us that a “bed was available.” This type of torture is indeed next level. I checked my emails incessantly, answered every phone call frantically, and couldn’t figure out why all the random strangers I drove past on the street or walked by in the stores were so goddamn happy. I was miserable. I was scared. I was helpless. Yet, I was baking Christmas cookies, wrapping gifts, and celebrating Christmas as if nothing was wrong. I started telling family members and a few close friends what we planned to do with Sydney. I didn’t need reassurance; I needed support. I needed my people to understand my child was suffering, and for the first time in a long time, I said, “I need you.” I needed their love, their grace, and their kindness because I knew the road ahead of me was going to be hard as hell.

We decided to tell Sydney a few days before she left. We discovered Sydney had gone through my email one day prior and read through the correspondence with the admissions team at the treatment center. She didn’t have the exact details, but she knew what was coming 24 hours before telling her. Sydney asked a lot of questions, cried, and was angry. She also understood it was for the best. I will never know what the 72 hours were like for Sydney as she waited to enter treatment. I’d imagine they were lonely, scary, and confusing.

We were almost home from dropping Sydney off when Andrew broke the silence between us. He said, “This feels unnatural. We are her parents, and yet we just left her with strangers”. I mumbled in agreement, in part because I agreed with this sentiment and in part because I didn’t have the energy to speak. I thought of this statement repeatedly during the first week of treatment. IT IS UNNATURAL! It’s unnerving and devastating to realize that you, as a mother, the person who gave birth to the child, cannot give her what she needs to be happy. In fact, it is the opposite; you seem to be the source of your child’s anger, frustration, and depression. You are blamed and hated. Everyone around you will tell you that you are doing the right thing and that you are a wonderful mom for getting your child help, but, ultimately, you feel as if you’ve failed.

Sydney entered treatment on a Wednesday. Andrew and I finally left the house on Saturday to grab lunch. We ate quickly as Andrew updated me on a work project. I passively listened. I unconsciously decided that life would not go on while Sydney was in treatment. I wouldn’t engage in fun activities, I couldn’t do date nights, and I certainly could not handle social media and all the Holiday happiness exploding on every profile. I genuinely try to support Andrew with his company and understand the importance of actively listening to him when he shares ideas, concerns, or stories about all things business. However, I failed this day. He asked me why I wasn’t responsive, and I essentially told him I couldn’t do work talk or any talk. I told him I needed a pause. I knew this wasn’t a healthy coping skill, I knew it wasn’t serving me, but I also couldn’t pull myself out of the shame I felt for leaving my daughter.

I admitted to family and close friends how scared and sad I was about Sydney entering treatment, but I never addressed my shame. Andrew and I got home from lunch and sat in the car as I cried (a rather ugly sob), yelled, and felt all the feelings I hadn’t allowed myself to feel for a very long time. I said the things I needed to say aloud, “why is this happening to us?” “Did we do everything we could?” “What if we would’ve done…?” I finally allowed myself to say, “What happened to her? She was so happy, remember…she was so happy? I should’ve done something different…I should’ve spent more time with her…” and so on. Andrew sat with me in the car and allowed me to emotionally vomit…everywhere! I cried until there were no tears left to cry. Then, I realized I broke the promise Andrew and I made to one another. I said I wouldn’t take things out on him, and we weren’t supposed to turn on one another. Yet, here I was just three short days into treatment, and I was shutting him out because I unconsciously decided life was on pause.

At that moment, I realized just how much shame I carry with me surrounding Sydney’s situation. I could no longer hide the blame I placed on myself for Sydney’s anger and unhappiness. I could no longer deny my unconscious decision to shut people out when I needed them more than ever before. I knew the coming weeks would be challenging. Still, there was no way to properly prepare for the overwhelming emotions that crisscrossed my brain each day. Andrew eventually told me we would “take it one day at a time.” This wasn’t revolutionary wisdom or Ted Talk worthy, but it’s what I needed at that moment. The simplicity of those words slowed the sobs, eased the emotional shit storm, and steadied my breathing as I prepared to walk inside and face my other two children. Madilyn and Lola needed to know that our little family would be okay. We would take the next few weeks just one day at a time and accept all the feelings and emotions that come when life gets messy.

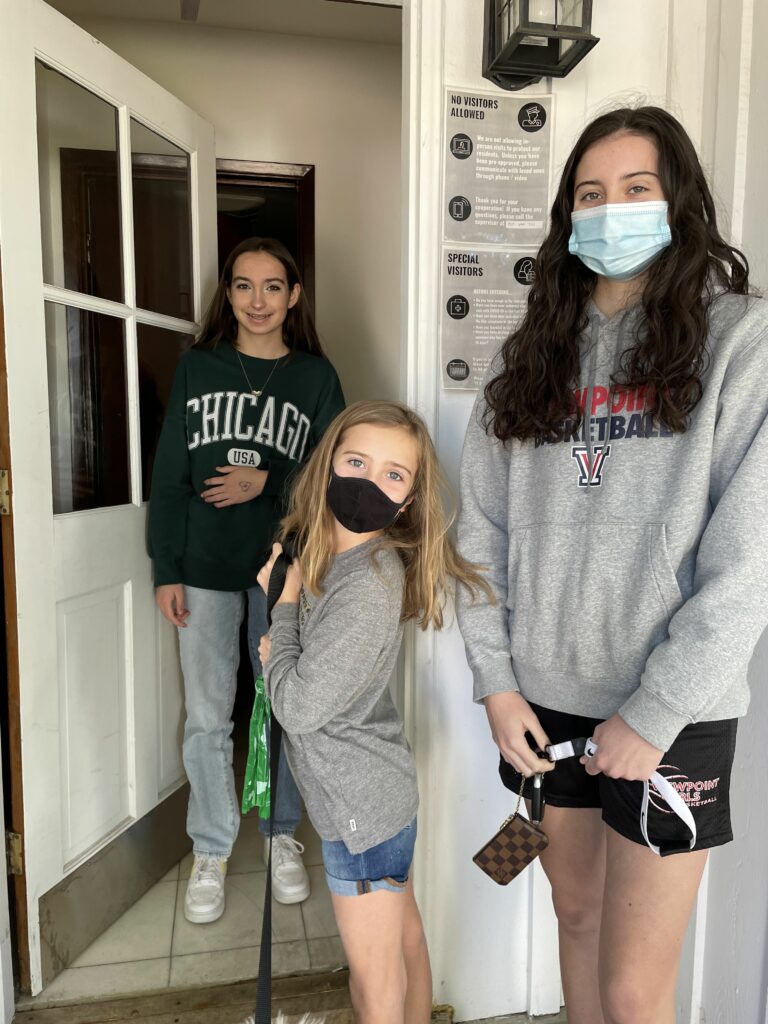

Emotions regulated, and things eventually felt somewhat normal. There was always a tinge of guilt when we went out to dinner or watched a movie. Anything fun provoked a feeling of guilt and grief, but I also knew that Madilyn and Lola needed peace, calm and deserved this time with Andrew and me. I focused on the daily phone calls I had with Sydney, the zoom visits each week, and the subtle hope each of us carried through this process. I was doing my best to take things one day at a time, despite how difficult it was. Then, Saturday, January 22nd came. Sydney’s 15th birthday. She celebrated with strangers, therapists, and mentors. The facility planned a fun outing, and they got “takeout” for dinner. However, the thought of her being with them and not us was sheer torture. We were allowed to stop by and say hello for 5 minutes. We had to wear masks, remain outside, and we were not allowed to hug her. We brought her a cake, cards, and a small gift. I stood on the doorstep of a residential treatment center and celebrated my daughter’s birthday in under 5 minutes. Again, unnatural!

Each day brought a new challenge when Sydney was in Residential Treatment. I didn’t make it through a single day without crying for the first two weeks. It didn’t get easier; I just became numb to the feelings. I am a big self-help junkie, reader, and podcast listener. I knew I should be doing work on myself and for myself when Sydney was gone. I tried. The podcasts, books, and meditations weren’t resonating at this time. They weren’t helping because I was in survival mode. Most days consisted of meetings with therapists and evaluators. Sessions were long, exhausting, and seemed to go in circles. There is no guidebook with instructions on navigating life when your child is in a treatment center. We did the best we could, and I believe that.

Our best was messy, flawed, and unpredictable. Our best was also honest. We told people the hard truth when asked where Sydney was or how she was doing. We encouraged Madilyn and Lola to do the same. We leaned on friends and family more than we typically do and appreciated each time someone would call or text to make sure we were okay.

Those four weeks were more painful than imagined. There is no silver lining or lessons learned. There is no takeaway. Having a child who requires extra attention, mental health treatment, and medical care like Sydney is excruciatingly difficult for the entire family and the child suffering. Every medication, treatment, and therapist is a gamble, an exercise of hope and prayer for what could be. Saying the words aloud and telling people our truth is possibly the only way to stay sane.